Botanical Voices and Imperial Legacies in Johanna Binder’s “Talking Land”

15. Oktober 2025

Biljana Puric

With three works on display at Galerie 5020, Johanna Binder reveals the entanglement of botanical histories with imperial ambitions

Plants have fuelled imperial expansion. They were not just passive inhabitants of the land but active contributors to its political, social, and economic histories. Johanna Binder’s Talking Land exhibition probes precisely this notion, critically examining plant agency through the lens of Ascension Island in the Atlantic.

Through a semi-translucent white curtain that encircles the presentation, vertical forms are noticeable, yet not fully readable. Visiting the exhibition alone, and being the only visitor at the time, the experience felt cradled and controlled — it stirred ontological turmoil while seducing the senses. Beyond this flimsy barrier, simultaneously protective and inviting, the show comes fully into view: The vertical installations comprise a resin tondo composition of different plants, perched on a black rod at eye level (Untitled, 2025), and Talking Land (2025) that combines glazed ceramic forms and rods, which appears to be taking shape before one’s eyes. Set diagonally from them, a floor-set TV screen with two headphones plays a three-part video, Ascension: Blossoms of Power (2025) presenting the history of the island and giving voice to plants. Strewn across the floor and around the installations are heaps of black earth, a segment whose material presence evokes the idea of terra nullius[1].

Botanical Echoes of Empire

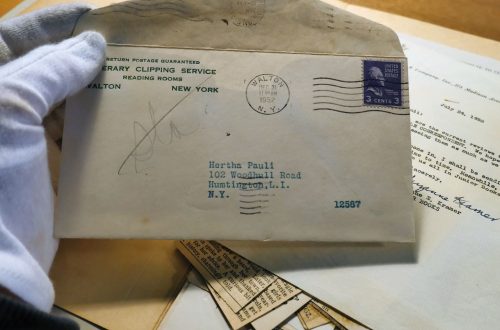

The forms at first seem familiar, but their strangeness emerges through the narrative the video presents. Over 330 plant species, which were planted on Ascension Island (first colonized by the British Navy in 1815) by Darwin’s colleague Joseph Dalton Hooker, transformed it from a barren, desiccated patch of volcanic rock into a productive, living, and habitable land. Most of them came from British colonies, representing the Empire’s reach across the globe and its politics of dispossession and exploitation hidden behind seemingly innocuous botanical explorations. Centuries passed, and today the island is a vibrant place of botanical diversity, political and military dominance, and technological advancement. NASA’s outpost, telegraph wires, an airfield, and GPS technology are all hosted on the island, shaping its significance and presenting an example par excellence of human intervention in nature.

The plants — or migrants, as they refer to themselves in the video, conversing via on-screen text accompanied by audio generated from their electrical signals — rooted their presence in humanity’s insatiable need to conquer and triumph over, revealing their complicity in this process through the metaphor of a wound, when they state: “We are writing history ourselves and digging our roots into the narrative like a finger into a wound that must not heal. We are digging up history, underground. We are your view of the world and more: what is, what is to come.”

Johanna Binder’s Growing Entanglements

Suddenly, the tondo, a form that celebrated human figures, religious topics, and historical events (e.g. Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo, 1504-1506), becomes more than a decorative depiction of plants. Crammed together and vying for attention, these plants usurp anthropocentrism and its traditional iconography. Here, they become new agents. This idea expands further in the Talking Land piece. Emerging from the ground and reaching upward, intertwined at the top and culminating in a formation that recalls both the Anthurium flower and a phallic shape, the glossy ceramic elements merge with the black rods to form a new organism. It is an epistemological overhaul, plants as new agents of knowledge, overwriting that produced by humans — it is a new process of othering and coming into being through entanglements with our histories rooted in masculinist expansionism and entrenched ontologies.

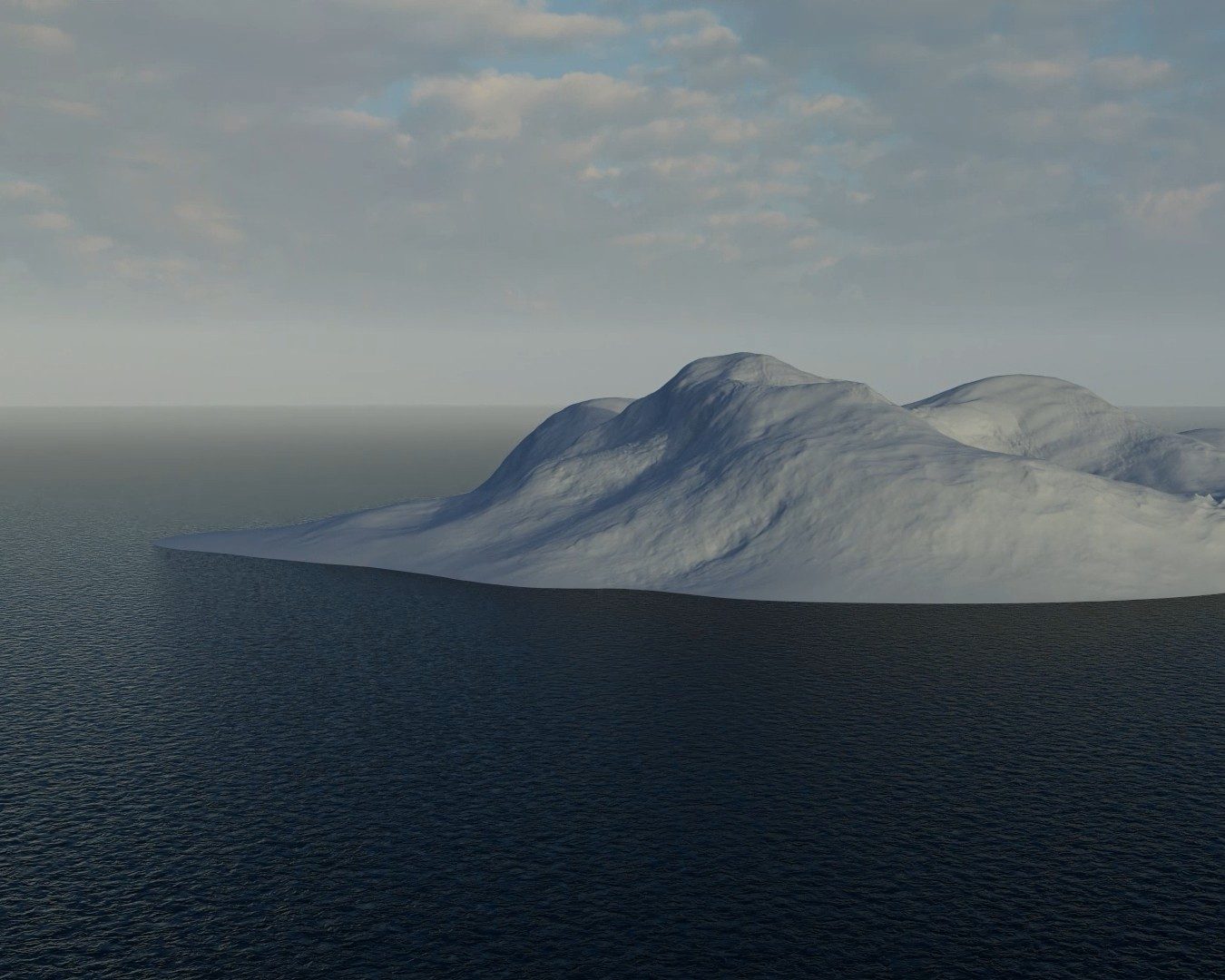

The Ascension video binds these ideas together. Starting with the historical, social, and political narratives surrounding the island, the second segment features Binder and her colleague, resolved to populate a rendering of an imagined island on their computer screen with Ascension plants. Resembling a video-game interface with avatars (plants) and their listed skills, the segment lays bare the biopolitical urgencies behind the selection process. The last segment gives voice to plants, who examine their histories. They evoke familiar tropes of indigeneity and migration, of working the land and being ruled over, of being active participants in history and mere passive presences.

The artworks’ effect is one of historical and conceptual usurpation. The pieces at Galerie 5020 decenter the human subject, expose the other-than-human entanglements in imperial expansion, and open up possible trajectories for rethinking these relations. They comprise a multilayered exploration of imperial heritage on the world’s margins and its implication and investment in the current state of affairs. The future may not yet be decided, but its outlines are presently coded and guided by an urge for perpetual progress that bites like an open wound. Talking Land takes stock of this in a presentation that, while observed from the outside, obfuscates these entanglements, requiring entry into its very centre to see and understand it clearly — from the givens visible above the ground to the undercurrents that shape it from below.

Footnotes

[1] Latin for ’nobody’s land,‘ a legal term referring to territory that could be claimed by imperial powers.

Das könnte dich ebenfalls interessieren

Verwobene Geschichte(n) schürfen

Oktober 24, 2025

Plötzlich Materie. Rose English im Museum der Moderne

April 21, 2025